Nature of Sharing

Record No. 1

Hey,

So I didn’t intend for my first actual post to be about anxiety and its manifestations. It wasn’t even on my mental list of upcoming topics that I knew I wanted to write about. But recently it’s been on my mind, mainly because my relationship with it suddenly changed and I’m sort of confused all over again. Ha! I guess sharing this could be a nod to how our self-perceptions, projections, and trauma-responses can participate in the ways we form bonds and exchange knowledge.

***

Over the last few months, I’ve been working through a particularly difficult period of my early adulthood about 5-10 years ago, which I had, until this point, consciously shoved to the back of my brain. I was aware of its presence, but would only note it in passing and quickly move on.

I considered this period factually, explaining away my experiences as if describing something casual like grocery shopping. No emotional attachment—just what happened and when. I successfully materialized a string of traumatic years into a learning experience, emotional growth, a lesson. In this way, I made it easy to dismiss.

Now I’m peeling it open again. I spent years reviewing this period from behind a net of logic and rehearsed verbiage. This time, I’m trying to feel my way through.

Anxiety is based around speed, an urgency, a timeline. It’s an impending element that does not passively wait for me, but encroaches. It moves towards me on a psychological terrain as I continually step back, creeping into the space I was standing on seconds before.

I think many of us have become accustomed to the effects of anxiety, to the point where we experience it recurringly—perhaps frequently. Although we could name some of the overarching reasons for our state of anxiety (labour, white supremacy and state violence, global warming, alienation, etc.), it can manifest in our bodies discreetly. I often can’t recognize when I’m feeling anxious anymore. It wasn’t until a few weeks ago, when I was explicitly asked what my body was doing while talking about some of my experiences, that I noted the physical ways anxiety takes hold. It’s more subtle than panic but more aggressive than sadness. It has debilitated me for long enough that I forget to notice; I get so distracted by verbal language that my bodily cues of risk and fear flatten into the background.

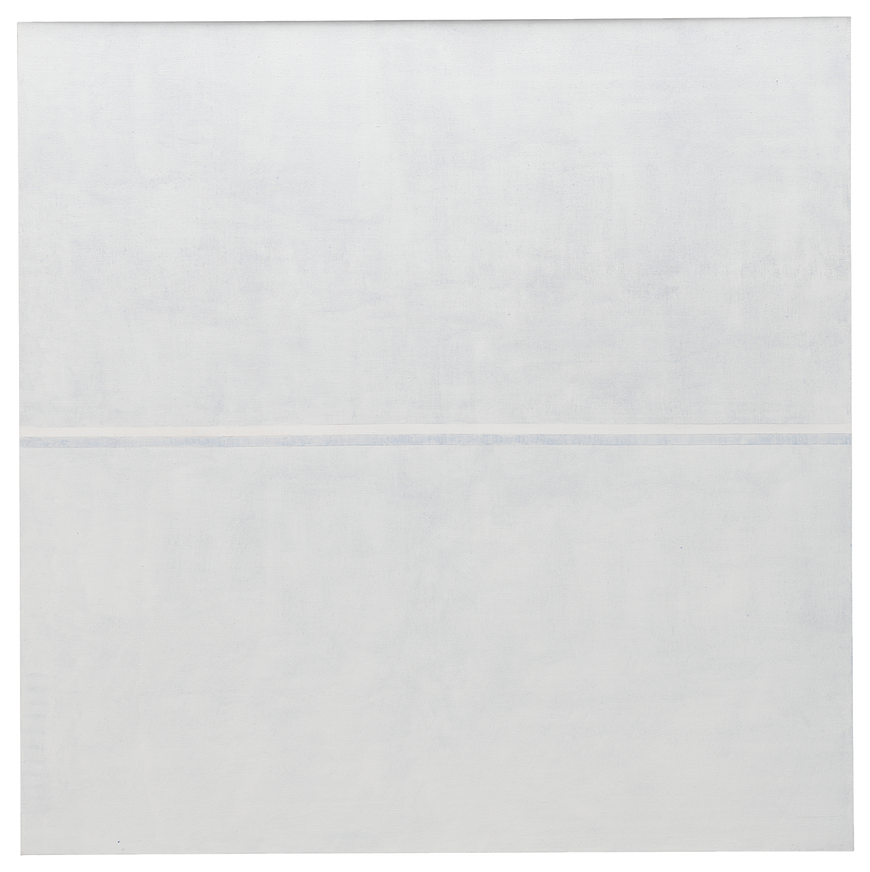

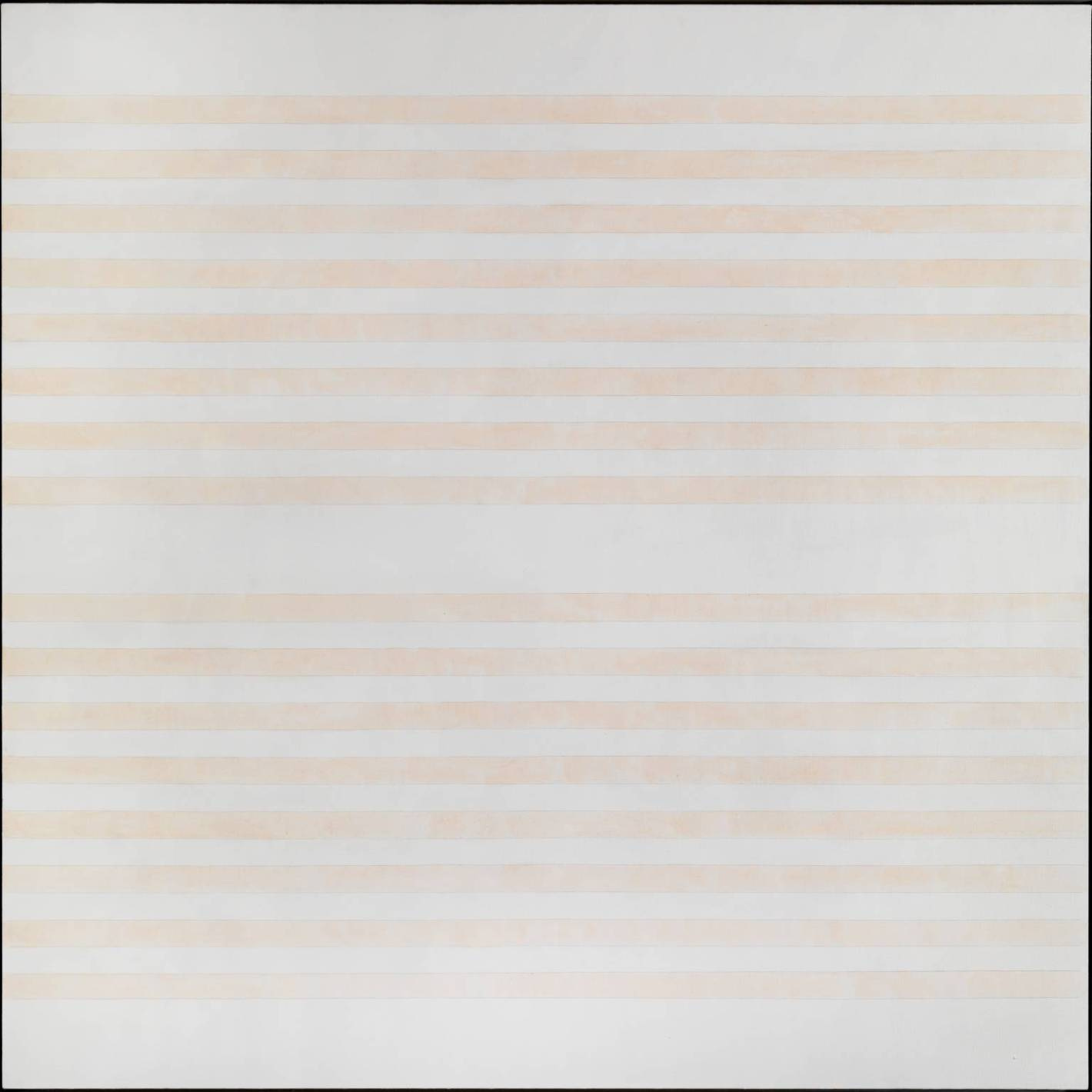

How then, does thinking about an event and feeling an event intersect? I’m reminded of a section in T Fleischmann’s Time Is the Thing a Body Moves Through, where they saw a series of works by Canadian abstract expressionist artist Agnes Martin:

[Martin] didn’t talk much herself, which is good, that her work is kept a bit removed like that. ‘When you’re with other people, your mind isn’t your own,’ she once said, and although she was talking about perception, and connecting to the realm of feeling, I think about language, too. Can you be alone with language? What a dream that would be, what a nightmare.

I once read about how Martin didn’t consider her paintings to be about structure, but about feeling. That she would look at a finished canvas and know whether it was complete or not—whether it expressed what she sought to express. The finish line was not attached to a solution or logic, but the primal nature of sharing. When I first fantasized about being alone with language, I was lured by the potential of archiving my environment. Perhaps decoding it by assigning purpose. But I quickly remembered that language’s power is relational. I can rationalize upsetting experiences as much as I’d like, but the unknotting only begins with a feeling.

Fleischmann goes on to describe their visit in the museum:

Jackson and I don’t say anything after entering the Agnes Martin room and we start to walk quickly. I’m surprised that I’m uncomfortable—how silent the Agnes Martin paintings are in the silent room. The loudest thing is probably the resonance of one pink, pale pink, or green past where its color ends, the line a small border but it changes everything, and even this is pretty quiet.

Yesterday, I thought about how revisiting difficult experiences (for the first time without language) stained my week with quietude. It felt like mourning, which we all do differently, but for me has felt akin to waiting. Not for anything in particular. Maybe for the feeling to pass, but it never does. My emotions were muted like vapour resting around my body.

I remember the first time I saw a series of Agnes Martin paintings in person when I was a teen. I knew minimalism and abstract expressionism were significant movements within the art history canon, but my visual impression of these works were usually underwhelming. Again, my logic-driven brain refused to investigate beyond noting the skill required for geometric precision. Seeing Martin changed that. She showed me the meditative quality of looking. She pulled my gaze into a warm trance, blurring my vision until looking slid into feeling.

This is to say that as much as I feel connected to the elements that surround me—a stranger waiting near me for the same bus, the shoreline, chalked hopscotch on a sidewalk— I have neglected a large part of myself by assigning it away to language. Language fills many gaps for us, but it also shapes the systems that indoctrinate us.

Much later in Time Is the Thing a Body Moves Through, Fleischmann writes,

Sometimes the broader cultural and political problems align with the personal exigencies they create, like a bounced check followed by a rise in unemployment, but more often there’s an uneven rhythm to those connections, a white blood cell count and then silver ocean and then a distant war. Like I grew up thinking I was singular, but the world kept revealing itself to me, until I understood that I was not.

Maybe to resist the oppressive tendencies of our anxiety is to affirm its presence. Marking its traits, cues, idiosyncrasies. Although I didn’t grow up thinking I was singular largely due to my cultural and religious upbringing, everyday still proves a new causality between us. To witness moments of connection without openly engaging with my own heavy past must somehow be a disservice, I think. Maybe I’ll know soon enough.

See you next time!